What Is Earth For?

What Is Earth For?

In 1960, when I was born, the world was completely precedented. Three years earlier, the USSR launched Sputnik into orbit. Rachel Carson’s prescient warning Silent Spring was two years away. Earth Day wouldn’t happen for another decade. The Internet wasn’t even a gleam in an engineer’s eye. The term ‘global warming’ would not debut for another fifteen years. The carbon dioxide content of the atmosphere was 317 parts-per-million (ppm) – still within normal going back two million years. Sixty years later, we’ve added 100 ppm and pushed the climate system to a precipice. In 1960, the world’s wildlife was largely intact and seemed safe. Today, one million plant and animal species are threatened with extinction and land degradation is widespread. In my lifetime, humans went from a having a small impact on the planet to being the predominant force for unprecedented change on a geological scale. Sixty years!

As evidence, here’s a graphic from a recent science journal. The researchers studied global indicators to understand how fast human impacts were taking place at earth system levels – i.e., to oceans, land, and the atmosphere. They discovered our impact had grown from small to colossal. The magnitude of alterations to the natural world was (and continues to be) unprecedented, they wrote, and humans are now the primary driver of change on the planet:

According to a paper published in 2018 in the Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences, there is a significant risk that increased warming will create self-perpetuating feedbacks, such as new carbon dioxide and methane emissions from melting permafrost in the Arctic, which could push conditions over a threshold that would put the planet on an irreversible “Hothouse Earth” pathway. In this scenario, temperatures rising another 3-4 °C beyond current 1 °C warming with devastating consequences.

Then there’s the Ice Age cycle. There are strong indications that the quantity of carbon dioxide already accumulated in the atmosphere has caused enough warming to push the earth out of the ice cycle that has existed for millions of years. Glacial conditions on the planet give way to warmer temperatures every 100,000 years. The oscillation between glacials and interglacials is predictable. However, according to scientists at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact the next glacial period may be significantly delayed – if it happens at all. “The bottom line is that we are basically skipping a whole glacial cycle,” said researcher Andrey Ganopolski, “which is unprecedented. It is mind-boggling that humankind is able to interfere with a mechanism that shaped the world as we know it.”

Hans Schellnhuber, a co-researcher, noted that we owe our fertile soil to the last ice age, which also created many familiar landscapes including glaciers, rivers, fjords, lakes, and moraines. Today, however, it is humankind that will determine the future development of the planet. “This illustrates very clearly that we have entered a new era,” he said, one in which “humanity itself has become a geological force.”

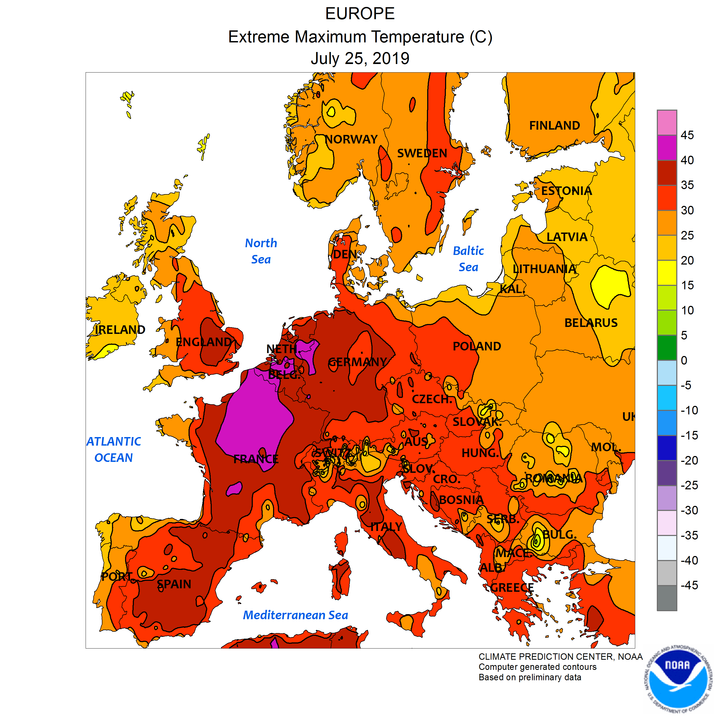

All of this hit home for me on July 25th, 2019, as Gen and I traveled from Berlin to Prague by train on a blistering, record-smashing day. It was a heat wave, as I learned later, but not just any heat wave. In Paris, the thermometer hit 108.7° F (42.6° C), demolishing a record that stood since 1947 by four degrees. Germany set an all-time temperature of 108°. It was a similar story in Belgium and the Netherlands where both countries hit 107°, burying previous highs by six and five degrees respectively. The Met office in England reported a reading of 101.7° at Cambridge University, breaking the previous record and marking only the second time temperatures had ever reached triple digits in the United Kingdom.

One meteorologist called the day astonishing. Heat records are usually set by a few tenths of a degree, but the marks that fell on the 25th were obliterated. No wonder our train compartment became a sauna! I could certainly sympathize with the passengers on a Eurostar train in Belgium that broke down and were not allowed to open windows or leave the train for three hours out of safety concerns. A passenger on the train was quoted saying “I have never been so hot in my life.”

The word unprecedented kept appearing in news accounts. Marshall Shepherd, a climate scientist, told a reporter that the shattering of temperature records “established an entirely new baseline.” Employing a medical analogy about a fast-rising fever, Shepard said “If you have a temperature of 99.6 degrees, it is alarming…103 degrees would send you right to the doctor.” Incredibly, it was Europe’s second heat wave. A scorcher in June also set temperature records (briefly) earning the month the worrisome title as the hottest June ever on the continent. It was also the warmest June ever globally, according to the World Meteorological Organization. There were heat waves in South Korea, Japan, India, the East Coast of the United States, and Alaska whose largest city, Anchorage, set an all-time high temperature on July 4th.

News stories confirmed the culprit behind the unprecedented heat. In an interview, Radley Horton, a climate researcher at Columbia University, said “The verdict is in: increasing greenhouse gas concentrations due to human activity – by raising average temperatures – have loaded the dice toward more frequent record-breaking heat extremes.” Karsten Haustein, a climate scientist at the University of Oxford, tweeted: “This. Is. Climate. Change.”

This avalanche of news came as a bit of a shock to me. I’ve worked in sustainable land,  water, and food issues for many years and I have studied the effects of climate change but none of the research I read said conditions would deteriorate this fast. James Hansen, an esteemed climate scientist, warned in his 2010 book Storms of My Grandchildren that heat waves would be more intense and frequent with each passing year unless greenhouse gas emissions were reduced, but I thought he was writing about the world his grandchildren would inherit! Apparently, it was arriving much more quickly.

water, and food issues for many years and I have studied the effects of climate change but none of the research I read said conditions would deteriorate this fast. James Hansen, an esteemed climate scientist, warned in his 2010 book Storms of My Grandchildren that heat waves would be more intense and frequent with each passing year unless greenhouse gas emissions were reduced, but I thought he was writing about the world his grandchildren would inherit! Apparently, it was arriving much more quickly.

Then in December, Australia caught on fire. Fueled by a multi-year drought, wildfires broke out in July and grew to catastrophic levels by early January 2020 under scorching temperatures. Smoke engulfed much of the eastern and southeastern edge of the continent, choking residents in Sydney and other cities. Ultimately, the fires burned 72,000 square miles of land (forty-six million acres), consuming more than a third of Australia’s forests. The fires caused the death of at least thirty-four people, destroyed nearly six thousand buildings, and killed as many as one billion wild animals including five thousand koalas, one-sixth of the total population. The catastrophe came to be known as the Black Summer.

Bushfires, as Australians call them, erupt every year but the ferocity and devastation of this conflagration was historic on a global scale. The President of the Australian Academy of Science, John Shine, stated that “the scale of these bushfires is unprecedented anywhere in the world.” Ironically, the fires were put out by torrential rainstorms that resulted in major flooding, requiring the evacuations of several towns. Sydney experienced its heaviest rainfall in thirty years. Extreme fire and flooding events are hallmarks of climate change. In March, an international group of researchers published a report that said human-caused global warming had a major role in amplifying the Australian fires by creating conditions that were thirty percent worse than they would have been in a world without the warming. It was a preview, they said, of things to come.

As the fires died down, a new global crisis emerged: the COVID-19 pandemic. Taken together, there’s been a lot of unprecedented taking place!

These events have put things into perspective for me. I have known for some time that we were careening toward a precipice from which we might not recover, but I always assumed we had time to take corrective action. However, the speed at which the world has approached the precipice – now only a few years away, say the experts – puts my personal journey into sharper focus. The transition from the ‘precedented’ world that I grew up in to the ‘unprecedented’ world that has begun to take hold has happened entirely within my lifetime. On the one hand, I’m not at all shocked. I’ve been worried about our destructive habits for nearly all my life, first through the lens of archaeology, then land conservation, followed by my activism with the Quivira Coalition. Figuring out how “live on a patch of land without ruining it” as conservationist Aldo Leopold once described the “oldest task in history” has been the central tenet of my work.

The anguished question now, it seems to me, is a big one: What Is Earth For? I’ll try to address this one here with old and new essays.