Essays

The Radical Center

The radical center is a place where people and organizations of diverse backgrounds meet to explore their shared interests rather than argue their differences.

Rancher Bill McDonald coined the term in the mid-1990s to describe an emerging consensus-based approach to land management challenges in the American West. At the time, the conflict between ranchers and environmentalists had reached a fever pitch, with federal agencies and others caught in crossfire. The radical center was a deliberate push-back. It was ‘radical’ because it challenged orthodoxies, including the belief that conservation and ranching were part of a ‘zero sum’ game – that one could only advance if the other retreated. The ‘center’ refers to a pragmatic middle-ground of partnerships, respect, and trust – and action.

An Invitation to Join the Radical Center

Twenty ranchers, scientists and conservationists wrote a declaration ending the grazing wars and inviting people to join the emerging radical center.

Originally read at The Quivira Coalition’s 2nd Annual Conference, January 2003.

Reflections From a “Do” Tank

“Recently, an acquaintance asked me what I did for a living. After explaining that I ran a nonprofit that worked with ranchers and conservationists in the Southwest on land health and sustainability issues, he said summarily “Oh, you run a Think Tank.” Without pausing, I replied “No, Quivira is a ‘Do’ Tank,” which elicited a nod and smile.”

Originally published in the Quivira Coalition’s Journal, no. 37, January 2012

Land Health: A Common Language to Describe the Common Ground Beneath Our Feet

This essay examines the language of land health as a basis for collaboration.

Originally published as Chapter Ten in Conservation for a New Generation, edited by Richard L. Knight and Courtney White, Island Press, December 2008

The Quivira Coalition

Introducing our effort to build bridges between ranchers, environmentalists, scientists, and public land managers.

Originally published in Range magazine, Winter 1999.

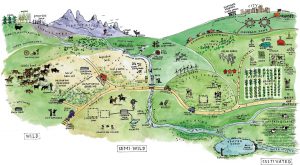

The New Ranch

The New Ranch implements land management practices that improve ecological and economic resilience across diverse working landscapes. It is based on the concept of land health, which is defined by the National Research Council as “the degree to which the integrity of the soil and ecological processes are sustained.” In other words, before land can sustainably support a value, such as livestock grazing, hunting, recreation, or wildlife protection, it must be functioning properly at a basic ecological level. If land is not healthy, then the value will be jeopardized sooner or later. As a grassroots movement, the New Ranch includes scientific documentation, public education, economic diversification, and ecological restoration.

The New Ranch: a Definition

A brief definition of a term that I coined back in 1997.

Originally published in The Quivira Coalition Newsletter (vol.7, no.4) April 2006

Prologue to Revolution on the Range: the Rise of the New Ranch in the American West

“In 1996, I had an anguished question on my mind: why didn’t environmentalists and ranchers get along better? In theory they shared many of the same hopes and fears – a love of wildlife, a deep respect for nature, an appreciation for a life lived outdoors, and a common concern for healthy water, food, fiber, and liberty. That was the theory anyway…”

Originally published by Island Press in May 2008

The Working Wilderness: a call for a Land Health Movement

Rethinking the conservation movement from the ground up.

Originally published by Wendell Berry in his collection of essays The Way of Ignorance, in November 2005

The Gift

Originally published as Chapter Ten of Revolution on the Range, this excerpt appeared in the journal Ecological Restoration, June 2009.

Mugido: Rethinking the Federal Commons

This essay explores a new vision for public lands based on collaboration and land health.

Originally published in The Quivira Coalition Newsletter (vol.7, no.4) April 2006

Grassbank 2.0

Building on what we have learned from the Valle Grande Grassbank.

By Courtney White and Craig Conley

Originally published in Rangelands, June 2007

A Corner Turned: The Chico Basin Ranch

An example of why the so-called ‘grazing wars’ faded away, thanks to ranchers like Duke Phillips.

Originally published in The Quivira Coalition’s Journal no. 29, October 2006

The Quivira Coalition’s first newsletter

In which we explain the purpose of The Quivira Coalition, the idea of the New Ranch, and debut my column “The Far Horizon”.

Originally published in by The Quivira Coalition in June 1997

The Carbon Ranch

The potential for large-scale removal of carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere through plant photosynthesis and related land-based carbon sequestration activities is both large and largely overlooked. Strategies and co-benefits include: enriching soil carbon, no-till farming with perennials, employing climate-friendly livestock practices, conserving natural habitat, restoring degraded watersheds and rangelands, increasing biodiversity, lowering agricultural emissions, and producing local food. Each of these strategies has been demonstrated individually to be both practical and profitable. A carbon ranch bundles them into an economic and ecological whole with the aim of reducing the atmospheric content of CO2 while producing substantial co-benefits for all living things.

The Carbon Ranch

This essay explores the possibility of large-scale removal of greenhouse gases from the atmosphere through plant photosynthesis and related land-based carbon sequestration activities.

Published in the Society for Range Management’s Rangelands magazine in April 2011

Originally published in the Quivira Coalition Journal No. 36, December 2010

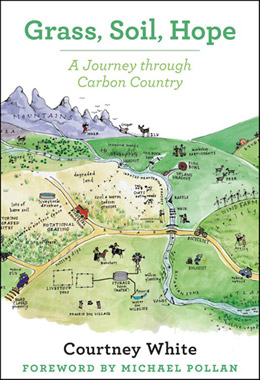

Prologue to Grass, Soil, Hope

“This is the story of how I came into Carbon Country. I’m a former archaeologist and Sierra Club activist who became a dues-paying member of the New Mexico Cattle Growers’ Association as a producer of local, grass-fed beef. For a boy raised in the suburbs of Phoenix, Arizona, during the heyday of sprawl, fast food, and disco music, this was a bewildering sequence of events.”

Originally published by Chelsea Green Press, June 2014

http://www.chelseagreen.com/bookstore/item/grass_soil_hope.

The Fifth Wave

Social movements are like ocean waves. They arise at a certain period of time, grow and become an effective agent of change for a while. Some succeed outright in their goals, some regain strength with fresh ideas and make another run at the shore, but many are carried out to sea by the irresistible tide of history. In the American West, the conservation response to natural resource depletion and crisis has followed this latter pattern. Since the late nineteenth-century, there have been four distinct waves of conservation. Each is now in a different stage of the ‘back-to-sea’ cycle, making way for an emerging fifth wave: agrarianism. This wave builds on the strengths and weaknesses of the previous waves as it meets the emerging conditions and challenges of the 21st century.

The Fifth Wave: Agrarianism and the Conservation Response in the American West

“Social movements are like ocean waves…They gather strength, grow and become an effective agent of change for a while. At their height, they either succeed outright in their goals or else begin to fade as circumstances evolve and their effectiveness declines. In the American West, the conservation response to natural resource depletion and crisis has followed this pattern. There have been four distinct waves of conservation—federalism, environmentalism, scientism, and collaboratism. Each is now in a different stage of the “back-to-sea” cycle, making way for an emerging fifth wave—agrarianism.”

Originally published in the Quivira Coalition’s Journal, no. 37, January 2012

Prologue to Age of Consequences

“This book was born on a sunny summer day in 2006 when I stepped out of a movie theater with my wife into the warm embrace of a lazy afternoon. Gen and I had finally found a convenient time to see former vice-president Al Gore’s inconvenient documentary on global warming with its dire warnings of environmental and social turmoil ahead if we maintained the Status Quo. Like millions of others, we were unnerved by what we saw. I was especially disturbed by the graphic images of rising sea water snaking through the streets of Manhattan, Shanghai and other low-lying cities around the globe. As we stepped off the curb into the parking lot, blinking in the bright sunlight after the movie, I quipped to Gen “We’d better see Venice, quick.””

Originally published by Counterpoint Press, January 2015

Four Farms…Down Under

“I had the pleasure recently of spending twelve days in Australia, visiting four amazing farms, giving a talk to a carbon farming conference, and having my brain saturated with a cavalcade of innovation. I also drank a boatload of instant coffee. I was impressed by Aussie inventiveness, by their open, upbeat, and nonconformist ways, and by their willingness to tackle topics that Americans shy away from…”

Originally published in the Farming Magazine, Winter 2011

Walking the Talk

“Talk of ecosystem services is all the rage today among academics, activists, agencies, and policy-makers. But for ranchers Tom and Mimi Sidwell, who produce grassfed beef in the high, dry plains of eastern New Mexico this talk is old news. That’s because they have been delivering ecosystem services for decades – they just didn’t know it had an official name until recently.”

Originally published in Acres (cover story), vol. 41, December 2011

Conservation in the Age of Consequences

An essay on how conservation might meet the challenges of the 21st century.

Originally published in the Natural Resources Journal (Vol. 48, No.1), published by the University of New Mexio School of Law, Winter 2008.

On Normality

A rumination on our chaotic world and the ‘little normals’ that make life worthwhile.

Originally published in The Quivira Coalition Journal No. 33, October 2008

$7 Gas and the New West

What would happen to the West if the price of gasoline hit $7 a gallon? It may not be as far-fetched as it sounds.

Originally published in The Quivira Coalition Journal No. 32, April 2008