My Story

An Unconventional Path

All my life, I’ve created right-brain responses to left-brain questions.

When I was thirteen, my parents sent me on an adventurous five-week trip to Mexico, full of romantic cities and mysterious ruins, igniting an interest in cultures, land, history, and archaeology that went deep inside me. I began asking questions. Who lived in these ruined cities? Where did they go? Why do civilizations rise and fall? The only tool I had handy to express my curiosity was a tiny X-15 Kodak camera. So, I took photographs. One image, shot through the teeth of a prehistoric stone jaguar, set me on a creative and unconventional path that I have followed ever since.

Returning home, I joined the Arizona Archaeological Society to pursue my questions. I attended monthly meetings and eagerly participated in a dig they directed in a prehistoric ruin on the edge of Phoenix. I even tried to decipher scholarly articles in the Society’s journal. The following summer, I volunteered at Pueblo Grande Museum, a city-owned archaeological park that protected a remnant of the mysterious Hohokam civilization. I worked on a professional excavation, built public displays, reassembled prehistoric pots, and had the pleasure of wandering the grounds alone, casting my imagination back to a long-lost era before the mythical Phoenix was consumed by fire.

A cascade of archaeology followed, including a volunteer stint in the ceramics lab of the A nthropology Department at ASU, where the staff was happy to have an energetic teenager wash thousands of broken pieces of pottery for them. Next came a month of ASU-led excavations of prehistoric sites in eastern Arizona, where I had the educational experience of watching graduate students at work and play, including drinking contests, water balloon ambushes, noisy broken hearts, and even a brief fist fight. Wow. Next summer, ASU hired me to work on an archaeological survey of land around Phoenix, part of the city’s decision to build a new dam to fuel its ceaseless growth. When I collected my first paycheck, at the eye-popping rate of $3.33 an hour, I was seriously amazed.

nthropology Department at ASU, where the staff was happy to have an energetic teenager wash thousands of broken pieces of pottery for them. Next came a month of ASU-led excavations of prehistoric sites in eastern Arizona, where I had the educational experience of watching graduate students at work and play, including drinking contests, water balloon ambushes, noisy broken hearts, and even a brief fist fight. Wow. Next summer, ASU hired me to work on an archaeological survey of land around Phoenix, part of the city’s decision to build a new dam to fuel its ceaseless growth. When I collected my first paycheck, at the eye-popping rate of $3.33 an hour, I was seriously amazed.

My archaeological adventure continued, including participation in a major ASU-led dig in downtown Phoenix, but I knew by then I wasn’t going to pursue the discipline. I wasn’t a scientist. I loved the hiking, camping and digging, the great people I met, the serious questions, and the seeking and finding involved but I hated math and statistics, preferring photography instead. My passion was creative, right-brain expression – a path I needed to follow.

Land and Culture

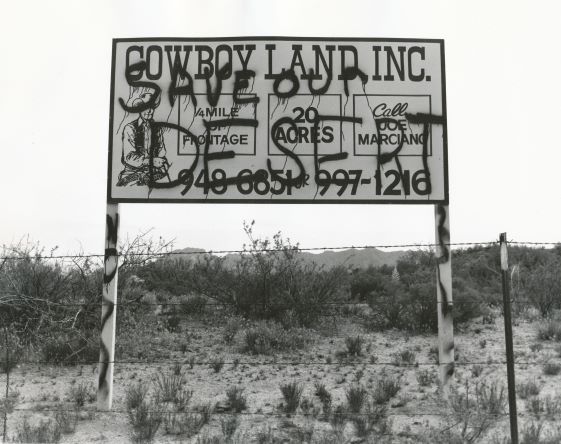

My archaeological experiences revealed a link between land and culture that fueled new  questions. In the early 1970s, my parents rented a derelict horse stable in the desert east of Phoenix and I spent many happy hours exploring the undeveloped land surrounding it. Our isolation didn’t last long, however. In shock, I watched the city grow relentlessly, eating the desert acre-by-acre, raising anguished questions. Why did we destroy land so thoughtlessly? Why were we so greedy? Was there no limit to our appetites? Watching Phoenix grow kindled a conservationist ethic in me that would eventually become a bright bonfire.

questions. In the early 1970s, my parents rented a derelict horse stable in the desert east of Phoenix and I spent many happy hours exploring the undeveloped land surrounding it. Our isolation didn’t last long, however. In shock, I watched the city grow relentlessly, eating the desert acre-by-acre, raising anguished questions. Why did we destroy land so thoughtlessly? Why were we so greedy? Was there no limit to our appetites? Watching Phoenix grow kindled a conservationist ethic in me that would eventually become a bright bonfire.

Other questions crowded in. In high school, an intense world history class fanned my interest in history into its own bonfire. Sumerians! Romans! Minoans! I underlined nearly every paragraph in the textbook (which I still own) and pestered my beleaguered teacher for more information. A class trip to England and Scotland the following summer made it all come alive – castles, cathedrals, kings, cricket. Then there was the land. A daylong hike in the stark hills near Ullapool, in western Scotland, made a deep impression on me. How does land shape a culture? Shape a person? What does it mean to belong to a place? Our memorable trip ended with a bang. It was America’s Bicentennial year and on the 4th of July we attended a huge firework show in London. No hard feelings apparently!

That fall I took a backpacking class, embarking on a period of hiking and camping. In 1977, I went on a backpacking odyssey in western national parks that blew my mind: Bryce, Zion, Grand Tetons, Yellowstone, and a week in remote Glacier. Fired up, I became president of the Backpacking Club at high school, energetically organizing trips and participating in some memorable misadventures. It culminated in a group hike along the 200-mile John Muir Trail in California’s high country. I began reading Edward Abbey and Wallace Stegner which opened a whole new set of questions for me involving public lands, tourism, wilderness, and conservation.

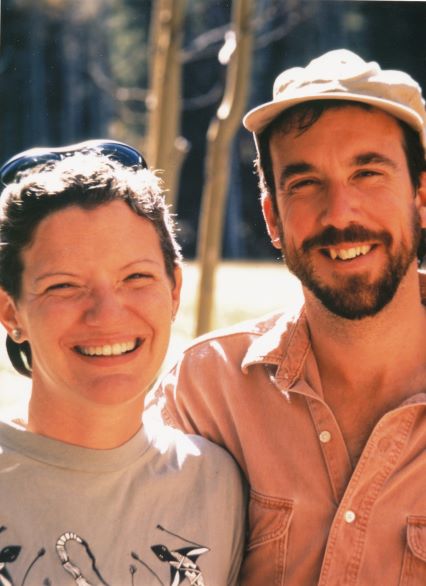

In 1978, I entered Reed College where I met Gen – the love of my life – in a  dormitory parking lot as we unpacked our vehicles before the start of freshman year. Over the next four years we did everything together, including tons of traveling around the Pacific Northwest, from the beaches to the mountains to the desert high country. In 1980, we drove from Albuquerque, where Gen lived, to Reed via national parks and forests on a road trip that I will always remember.

dormitory parking lot as we unpacked our vehicles before the start of freshman year. Over the next four years we did everything together, including tons of traveling around the Pacific Northwest, from the beaches to the mountains to the desert high country. In 1980, we drove from Albuquerque, where Gen lived, to Reed via national parks and forests on a road trip that I will always remember.

Reed exponentially expanded my left-brain questions. I became an Anthropology major with a focus on ethnography – the study of a culture in a particular place and time. For my senior thesis, I decided to pursue my visual interests and study ethnographic film. I was especially intrigued by the work of Robert Gardner, whose artistic films challenged conventional documentary idioms. I liked his heresy. Reed prided itself on subverting orthodoxies and I spent four years learning the art of healthy skepticism. Unfortunately, I floundered academically. Many Reed graduates go on to earn Phds but I knew early I wasn’t destined to be one of them. Undaunted, I chose for my thesis advisor the most intimidating professor on the Anthropology faculty and ended up earning an ‘A’ for an analysis of visual communication that was praised by my committee for its originality.

Meanwhile, my right-brain had been busy taking photographs. Exile, the student-run literary magazine, published three black-and-white photos I shot on the cross-country sojourn with Gen. That led to a job as a photographer and then editor for Reed’s yearbook, The Griffin. On a visual roll, I brought my father’s vintage 16mm movie camera to school, which led to a spate of amateur moviemaking, including a lampoon called Gidget Goes to Reed. During the summer I made two music video-type films, set to classical music (MTV debuted that August, I learned later). They were purely artistic endeavors. I wasn’t trying to answer anything left-brain. But it whetted my appetite. I took a class in Japanese cinema, enrolled in a film editing class at a Portland art school, and soaked up Australia’s New Wave of cinema at the indie movie halls.

The next step was logical: graduate school in filmmaking. I was thrilled when UCLA accepte d me into its famous program. Los Angeles! Enrolling in 1983, I intended to make documentaries, but quickly switched to fiction film. Overeager by nature, I took too many classes and put in too many long days in Melnitz Hall, mostly in dark rooms. I poured every bit of left-brain and right-brain energy I had into writing and directing an earnest dramatic film about archaeologists on survey titled Mostly Ash and Pottery. The effort exhausted me financially, emotionally and physically. I dropped out of school two classes short of an MFA degree. To recover, I took a job in Acquisitions department of UCLA’s main library, located in the basement. It was supposed to be temporary, but I had no plan for next steps in my life. I was stuck. My path seemed to go nowhere.

d me into its famous program. Los Angeles! Enrolling in 1983, I intended to make documentaries, but quickly switched to fiction film. Overeager by nature, I took too many classes and put in too many long days in Melnitz Hall, mostly in dark rooms. I poured every bit of left-brain and right-brain energy I had into writing and directing an earnest dramatic film about archaeologists on survey titled Mostly Ash and Pottery. The effort exhausted me financially, emotionally and physically. I dropped out of school two classes short of an MFA degree. To recover, I took a job in Acquisitions department of UCLA’s main library, located in the basement. It was supposed to be temporary, but I had no plan for next steps in my life. I was stuck. My path seemed to go nowhere.

The West

Two events in 1986 gave me renewed purpose: first, sleuthing by my aunt Sarah turned up William Faulkner as a not-so-distant cousin! That was both a surprise and an inspiration. I dug into his books and life. Second, a book came across my desk by John Nichols titled On the Mesa, about northern New Mexico. I suddenly felt myself emerging from underwater. Faulkner had the South. I had the American West. That would be my focus! I had no idea what that meant, but I would start by going ‘back to school’ and hitting the books. It was easy – I worked in one of the great research libraries in the region. I studied during breaks at work, at home, on weekends. I read about the West’s history, people, geography, literature, state by state, stack by stack.

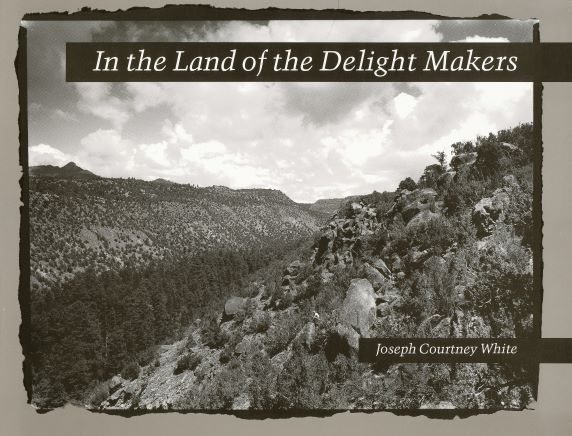

By early 1988, I was ready – but to do what? I had too many questions on my mind n ow. Where to start and how to express them? The previous winter, my film school mentor, Lou Stoumen, had graciously loaned me his medium-format camera and I had a grand time taking photos. I decided to try photography when an opportunity arose that summer. Gen was heading back to New Mexico to work on an archaeological survey for the National Park Service. I pitched a photo documentation project to her boss, Bob Powers, and he agreed so I went out and bought a medium-format Bronica camera. By June, I was hiking, camping, and shooting photos while thinking left-brain questions. I returned next summer for more photos – now I had a book in mind.

ow. Where to start and how to express them? The previous winter, my film school mentor, Lou Stoumen, had graciously loaned me his medium-format camera and I had a grand time taking photos. I decided to try photography when an opportunity arose that summer. Gen was heading back to New Mexico to work on an archaeological survey for the National Park Service. I pitched a photo documentation project to her boss, Bob Powers, and he agreed so I went out and bought a medium-format Bronica camera. By June, I was hiking, camping, and shooting photos while thinking left-brain questions. I returned next summer for more photos – now I had a book in mind.

I came up with an idea for a fine art photography project about the West’s famous frontier. It had closed in 1890, concluding a significant chapter in American history, which meant that 1990 would mark the centennial of this landmark event. My left-brain kicked in. Was the frontier dead or had it metamorphosed into something else? If it had, what was it exactly and what did it look like? I decided to find out with right-brain black-and-white photos. When I was done, I called Wallace Stegner out-of-the-blue and visited him at his house in California. He graciously wrote an Introduction to the photo book, an act of kindness that deeply impressed me.

In the meantime, my path took a memorable detour through Hollywood. My cousin Bil l Ragsdale, an actor, was a star in an early hit for Fox Television. He introduced me to his agent, setting off a flurry of screenwriting (I dabbled in short plays too). The agent was a charming fellow but going to his office was like entering a foreign land where I didn’t understand the language or culture. I wrote a story about a timber town in Alaska for him, which led to a meeting with a producer and a TV star…and went nowhere. I made $2000.

l Ragsdale, an actor, was a star in an early hit for Fox Television. He introduced me to his agent, setting off a flurry of screenwriting (I dabbled in short plays too). The agent was a charming fellow but going to his office was like entering a foreign land where I didn’t understand the language or culture. I wrote a story about a timber town in Alaska for him, which led to a meeting with a producer and a TV star…and went nowhere. I made $2000.

In 1991, Gen and I relocated to Santa Fe so she could accept a full-time position with the National Park Service. Needing a paycheck, I took a seasonal job as an archaeologist at nearby Pecos National Historical Park. I soon became involved in a highly left-brain research project involving academic questions about adobe bricks and architectural sequencing in the park’s Spanish colonial ruins. It resulted in a paper published in a peer-reviewed journal and a presentation at the annual meeting of the Society for American Archaeology (and a trip to New Orleans!). The right-side of my brain, meanwhile, demanded that I write a book about land and history based on my experience at the park. It was exciting and fruitful work, but I was stuck doing archaeology again. My path had grown faint.

The Quivira Coalition

On November 8, 1994, my world had changed dramatically. That was the day Representative Newt Gingrich and his co-conspirators staged the “Republican Revolution” in the mid-term Congressional elections, vowing to quickly overturn a generation’s worth of environmental legislation. I called the local office of the Sierra Club the next day. Soon, I was lobbying state legislators, writing op-eds, and organizing workshops among many other projects in what would be the start of a life-changing endeavor. Although I had been a member of various environmental organizations since my Reed days, with an interest in public lands and wilderness, I would now work in conservation full-time.

This work meant a new, urgent set of questions and answers. All were still centered on land, culture, and history – at least I thought so. Unfortunately, my anthropological bent created a great deal of tension with a group of hard-core environmental activists in New Mexico, particularly my insistence that the conservation movement honor local cultures and their traditional land-use practices. It was a period of high conflict between rural residents and environmentalists across the West. The struggle was mostly ideological, I learned. What was land for – use or preservation? Cattle or condos? Which competing vision of public land would prevail? Thanks to my Reed training, I kept challenging treasured orthodoxies in the conservation movement, which irritated my fellow activists. It made for uncomfortable meetings.

I decided to walk my talk. In 1997, I cofounded the nonprofit Quivira Coalition with a rancher and another conservationist. Quivira was our attempt to answer an anguished question that loomed large at the time: why didn’t environmentalists and ranchers get along better? In theory they shared many of the same hopes and fears: a love of land, a deep respect for nature, and a common concern for healthy water, food, fiber, and liberty. That was the theory. The reality was they were locked in a bitter struggle, exemplified by two popular bumper stickers: “Cattle-free by ’93!” shouted one. “Cattle galore by ’94!” shouted the other. Other anguished questions quickly followed: why was the land in such poor shape? Why were humans messing up the planet so badly? What could we do to heal relationships and work together? To answer this last question, we decided to work in the radical center with ranchers, a highly unorthodox idea at the time. By doing so we joined an exciting collaborative movement rising across the West.

Quivira was also a creative endeavor that allowed me to give talks, organize conferences and work shops, and think up new projects. There wasn’t a prepared path to follow, so I made it up as we went along. It was exactly like exploring a new land – which is what Quivira designated on old Spanish maps – requiring both logical thinking and gut intuition. Left brain and right working together. My work at Quivira focused increasingly on writing, editing, and storytelling. I learned that scientific and economic data tended to fall on deaf ears if there wasn’t an inspiring narrative. So, I began writing essays and short profiles of innovative people and practices for a general audience.

shops, and think up new projects. There wasn’t a prepared path to follow, so I made it up as we went along. It was exactly like exploring a new land – which is what Quivira designated on old Spanish maps – requiring both logical thinking and gut intuition. Left brain and right working together. My work at Quivira focused increasingly on writing, editing, and storytelling. I learned that scientific and economic data tended to fall on deaf ears if there wasn’t an inspiring narrative. So, I began writing essays and short profiles of innovative people and practices for a general audience.

I caught the attention my hero, Wendell Berry. In 2005, he included my essay The Working Wil derness in his collection The Way of Ignorance, an endorsement that set me on a right-brain path to many articles and books, including Revolution on the Range, Grass, Soil, Hope; The Age of Consequences; and Two Percent Solutions for the Planet. Many of the questions that I tried to answer in these writing projects were motivated by my concern for the world our children, Sterling and Olivia, would inherit.

derness in his collection The Way of Ignorance, an endorsement that set me on a right-brain path to many articles and books, including Revolution on the Range, Grass, Soil, Hope; The Age of Consequences; and Two Percent Solutions for the Planet. Many of the questions that I tried to answer in these writing projects were motivated by my concern for the world our children, Sterling and Olivia, would inherit.

The Age of Consequences

In 2005, Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans – raising very anguished questions. The specter of climate change loomed suddenly, among other challenges. My path took a new turn when we added the word ‘resilience’ to Quivira’s mission statement and began to focus our work on the big picture. I called this period of time for the nation the “Age of Consequences” and wondered what lay ahead, so I began writing a chronicle on my web site.

Meanwhile, we had become ranchers. In 2004, Quivira took over the 36,000-acre Valle Grande allotment on the Santa Fe National Forest, becoming permittees. We also became dues-paying members of the New Mexico Cattlegrowers’ Association – which was not something this city boy and environmentalist ever expected! It marked a period of intense focus on social change, including front-line participation in the local food movement as producers and marketers of grassfed meat from our Rowe Mesa ranch. We started a Journal focused on the emerging agrarian movement, implemented an apprenticeship program for young people on progressive farms and ranches, greatly expanded our riparian restoration program with Bill Zeedyk, and worked closely with the Ojo Encino Chapter of the Navajo Nation on rangeland and food projects. In 2008, I had the honor of attending Terra Madre in Turin, Italy, as a food-producer (bringing Europe into my life).

It was a period of extensive travel for myself, Gen and our young children, Sterling and Olivia. We visited ranches and farms and national parks (Yellowstone was a favorite) and made our way to Europe twice. I began an informal right-brain photography project during these trips, which I eventually called This Moment In Time, suspecting I was documenting something important taking place in the world, for better or worse. I was keeping a close eye on climate change now, following news stories about rising carbon dioxide levels and asking anguished questions about what we could do to help.

In 2010, we reluctantly sold the Valle Grande ranch and dropped out of the local food movement, a casualty of the economic recession that followed the meltdown on Wall Street. The left-brain questions were daunting now and somewhat gloomy, pulling my spirits down. Fortunately, in 2010 I discovered carbon, which cheered me up. There was hope and right-brain things we could do. I threw myself and Quivira into exploring carbon country, writing books, giving talks, and organizing educational events.

Unfortunately, grassroots social change was coming too slowly to match the rising challenges of the new century. Partisanship had deepened, orthodoxies held firm mostly, and the Status Quo prevailed at national levels. It was discouraging, so I decided to take a different path. I wanted to find my ‘inner Faulkner’ and write books. In 2012, I turned the reins of Quivira over to the next generation and became the organization’s Creative Director.

In 2015, the term ‘regenerative agriculture’ emerged in the wider grassroots community to describe our collective work. This was good news. Its practicality and hopefulness are the counterbalance to the challenges we all face, particularly the on-the-ground effects of a warming world. It was the right umbrella for us to gather under. It was against this backdrop of hope and concern that I watched the world pass a critical climate threshold (400 ppm), including a memorable trip to Paris at the end of 2015 to participate in activities linked to the pivotal climate talks. A month later, I left Quivira to focus on writing and regeneration.

In 2017, I began co-writing books on regenerative agriculture with busy farmers, ranchers, and nonprofit directors as a way of helping them tell their stories. I wrote fiction too, including a mystery set on a ranch in northern New Mexico.

Today, the anguished questions have become exceptionally large, encompassing the earth and all life on it – including a global virus pandemic, of all things. I can say from personal experience that the world has changed profoundly in just a few decades – from the ‘precedented’ one that I grew up to the unprecedented one we now occupy. As the planet warms, the anguished questions have a haunted feel. Where are we going? What is the earth for? What are we for?

I’ll keep searching for answers, but I’d like to share what I’ve discovered so far along my path – and remember.

~~~~